History (and wargaming) writing

The below excerpts are all from Do You Want Total War?, my novel which was published in 2013. Do You Want Total War? is available for purchase through Amazon and other online retailers both in hard copy and Kindle/Nook/ePub formats; more information can be found at the book's Amazon eStore and Facebook page.

DYWTW Excerpt 1: The Beginning

From Do You Want Total War?, beginning at the start of the Prologue:

I’m looking at Dennis, across the thin stacks of cardboard that define our mutual hostility. He adjusts his eyeglasses, apposite wide rims of black plastic around oddly thin lenses, and plucks at his scraggly, mottled beard with thumb and middle finger, pausing periodically to inspect the tips or scrape a fingernail across one of his lower incisors. I hate watching Dennis pluck at his beard. I’m not old enough to grow a beard, so my expertise here is limited, but I can’t help thinking that he will smear grease into everything he touches, or that Dad will eventually find tiny brown and grey hairs on or in something he cares about. Also, Dennis seems awfully casual about the hair on his chin when he has so little left on the rest of his head. Not that I would choose to look like Dennis, but if I had his beard and wanted to remove it, a shave would be more decisive.

DYWTW Excerpt 2: On Luck in War

From Do You Want Total War?, Part One, after a discussion of the luck factor in poker:

I’m not saying I prefer games with no luck – if I did, I’d play chess and not Totaler Krieg. And certainly, games that attempt to simulate history should incorporate randomness. Real generals can’t feed perfect variables into a computer and know how their strategies will unfold on the battlefield; when I attack Tripoli at 2:1 odds and roll a ‘6’, I’m able to imagine any number of reasons why my attack might have failed. Bless the English department at Muhlendorf for making me read this passage from Stephen Vincent Benet’s John Brown’s Body:

DYWTW Excerpt 3: Learning About War

From Do You Want Total War?, Part Two, explaining how Sean (the narrator) started becoming interested in history:

On my eighth birthday, my parents gave me a copy of The American Heritage Picture History of World War II. Although I’ve worn out the book’s binding, to the point that pages snap away from the spine if I turn them carelessly, I still look at it from time to time. Its 610 pages of text hold up surprisingly well, but its 720 photographs were its star attraction to a young child who had never felt history come to life before. I had only ever lived in full color, and the black-and-white world of those pictures was impossibly exotic to me, even before I first noticed the Spitfire’s elegant curves and the meticulous angles of an Essex-class aircraft carrier’s flight deck. (I myself have moved on from such mechanical fetishization – I’m a “form follows function” guy when it comes to such things, and the Spitfire drawing hanging above my desk at home is a prepubescent relic – but many history geeks never do, and I can understand why.)

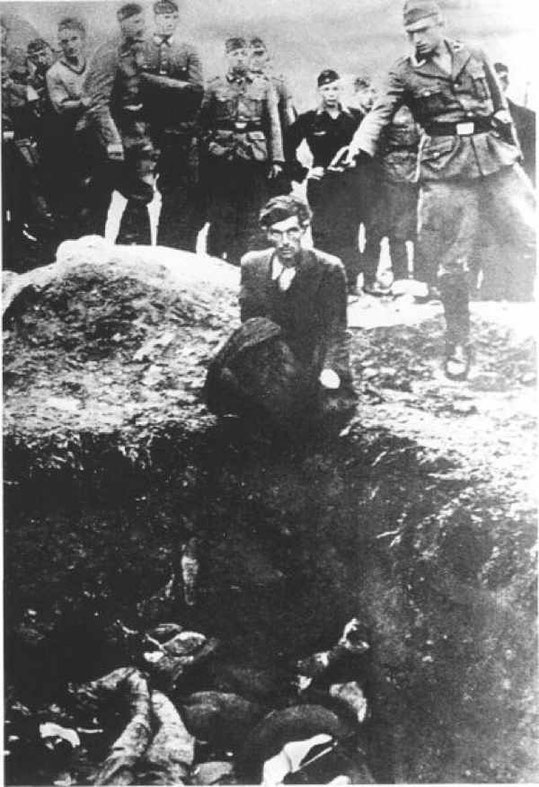

Among the book’s many images detailing the horrors of war is a picture I still can’t shake. Its central character is a gaunt figure, a man likely of Jewish origin with long, Slavic cheekbones. He stands at the precipice of an open mass grave, staring forlornly and uncomprehendingly at the camera, with dead bodies visibly stacked beneath him at the bottom of the photo. To his right is a German soldier, pointing a pistol at his head; behind him is a queue of other men and women in civilian clothes, each shepherded forward by other soldiers and waiting in turn to receive a bullet in the brain. It’s a haunting picture that asks me many questions, both metaphysical and mundane: What goes through a man’s mind, seconds before being murdered? Why would the victims simply queue for their fate like that and not offer resistance or try to escape? How could anyone impassively photograph a scene like this? When the photographer finished developing his film, how much would his sense of professional pride at the quality of his work be tainted by any understanding of what he had witnessed? How does a photographer come to be at that place at that time to take that picture? Was he the Wehrmacht’s official Chronicler of Atrocities, had he signed up as a war correspondent and made a regrettable career diversion, or would he have gladly traded his Leica for a Luger and shot the victims himself? Is a pistol really the best weapon with which to conduct mass executions? What happens to the queue of victims while the executioner loads a new ammunition clip, or when he runs out of bullets altogether and has to wait for a new supply – does everyone just shuffle their feet in embarrassment, like supermarket patrons when the checkout lady calls several times over the loudspeaker for a price check? Or do different shooters take turns, like blackjack dealers in a casino?

DYWTW Excerpt 4: Study Tangents

From Do You Want Total War?, Part Two, as Sean (the narrator) meets up with Becs (one of his classmates) for the first time:

Three days before my first-trimester AP European History final exam, Becs comes to my house for our first study session. She arrives just after sunset; as I open the front door, she’s waving goodbye to her mother. “Mom needs the car tonight,” she apologizes. She’s wearing blue jeans and a demure white cardigan beneath her brown, suede jacket.

I lead Becs to the soft seats of the living room, where we quickly swamp the coffee table with backpacks, textbooks and study notes. “How do you want this to work?” she asks.

“I’m open to suggestions,” I respond. “What areas do you want to focus on?”

“All of them,” she says. “But then, you’re the one who could teach our class, so perhaps you should choose. I don’t want this to be boring for you.”